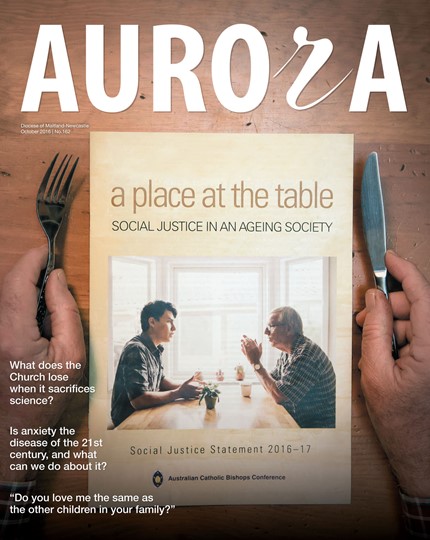

The royal commission’s Final Report is due in November this year and we wonder just how more damning it can be. More shocking stories have been revealed since the Interim Report.

The royal commission says many of the issues identified in previous reviews and inquiries persist, despite the actions of successive governments. It is “difficult not to be critical of successive governments’ failures to fix the aged-care system” it said, but also noted the dependence on other sectors such as health and vocational education and training have added to the difficulty of implementing reform.

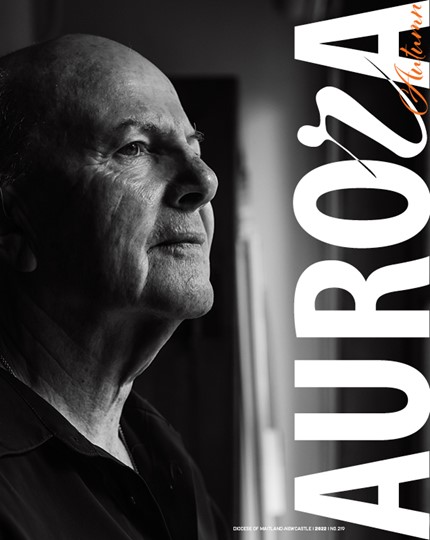

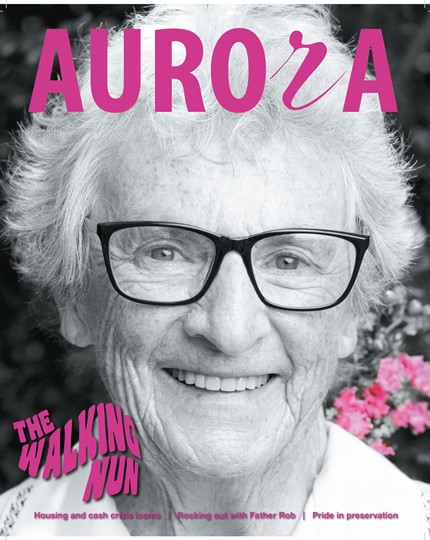

An ageist mindset persists, undervaluing older people, limiting their possibilities and using disrespectful language such as “a burden” and “an encumbrance” the royal commission concluded. It also expressed concerns about discussions relating to taxpayers’ ability to pay for old people’s dependence.

Nick Mersiades is director of aged care at Catholic Health Australia (CHA), and he says the immediate take away from the Interim Report is “a shocking tale of neglect”.

“The royal commission concludes that it has heard compelling evidence that the system designed to care for older Australians is ‘woefully inadequate’, that many people receiving aged care ‘are having their human rights denied’, and ‘their dignity not respected’,” Mr Mersiades said.

“The commission describes aged care as fragmented, unsupported, underfunded, mostly poorly managed, unsafe and ‘seemingly uncaring’, due to neglect at all levels – governments both federal and state, government departments and agencies and providers.”

Meanwhile, life goes on — just — for those “unlucky” enough not to be in care.

St Vincent de Paul’s Karen Soper manages Matthew Talbot Homeless Service in Wickham — which is partially government funded and provides specialist services supporting men and men with children. It also supports rough sleepers in the Newcastle and Lake Macquarie areas.

“Last year we assisted about 800 people and have noticed a steady increase in the amount of men aged over 60 years who have accessed our service and identified as homeless,” Ms Soper said. “Some of the common reasons for the increase in homeless numbers are relationship breakdown, isolation, unemployment, lack of finances and affordable housing, mental health and addiction.

“The assessment pathways are complex and accessing aged care is a long and arduous process. We would welcome a more collaborative approach to achieve accessible, respectful and quality aged care for the vulnerable in our community.”

Life’s clearly tough on the street for the aged. Yet those in care are frustrated, have feelings of despair and hopelessness, and are reluctant to complain, fearing their situation will worsen. The aged-care system lacks fundamental transparency, including around the performance of providers. The regulatory system intended to ensure safety and quality does not deter or detect poor practices.

Unfortunately, aged care is not a valued occupation. The workforce is under pressure, pay and conditions are poor, innovation is stymied, and education and training are patchy.

“The aged-care system has not kept up with changing needs and community expectations,” Mr Mersiades said. “Some providers appearing before the commission appeared to be defensive and ‘occasionally belligerent in their ignorance of what is happening in their facilities’, and reluctant to take responsibility.”

The Interim Report does not include any recommendations, instead highlighting three areas in need of urgent action. They are: the need for additional higher-level home-care packages to reduce waiting lists; the significant over-reliance on chemical restraint; and the flow of younger people with disability going into aged care.

Mr Mersiades said CHA has advocated the final response should also address the financial pressures residential aged-care providers face.

Volume 1 of the Interim Report dedicated itself to six “inconvenient truths” surrounding the aged-care system. These relate to accessing formal aged care and support; managing waiting lists; the inhumane use of restrictive practices; poor access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; problems attracting employees; and, the plight of almost 6000 people under the age of 65 years who are forced to live in residential aged care.

“What remains understated is that there is a seventh inconvenient truth,” Mr Mersiades said. “That is the reform directions the commission has identified will be expensive, and even more so when the baby boomer generation reach their 80s from the late 2020s.”