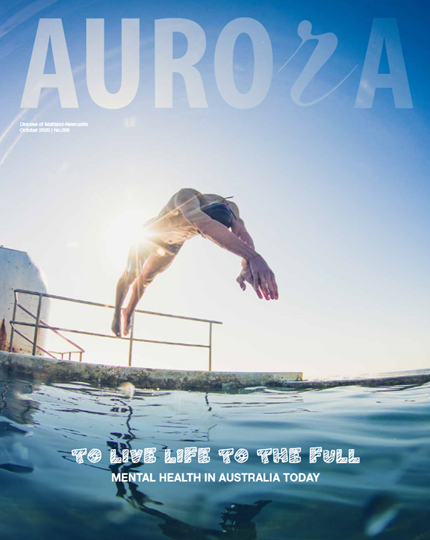

Many thousands of young Australians took part in the on-line survey for the forthcoming Synod in Rome on ‘Young People, the Faith and Vocational Discernment’.

Overall, their greatest concern was ‘Mental Health’. Now ‘Well-being’ and ‘Mental Health’ are buzz-issues among those who work with young people, so I was inclined to think that the survey response was perhaps a bit of a pre-programmed answer, as beauty queens used say their greatest desire was ‘world peace’. But I was wrong.

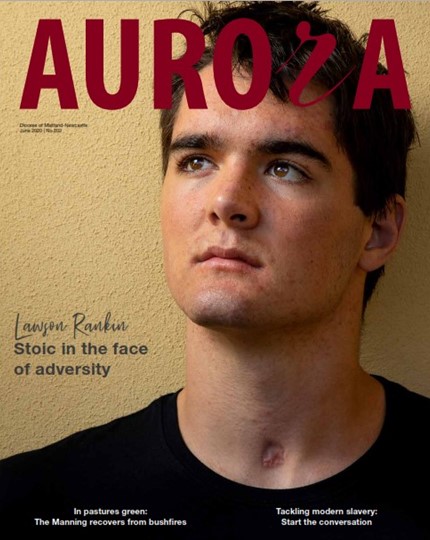

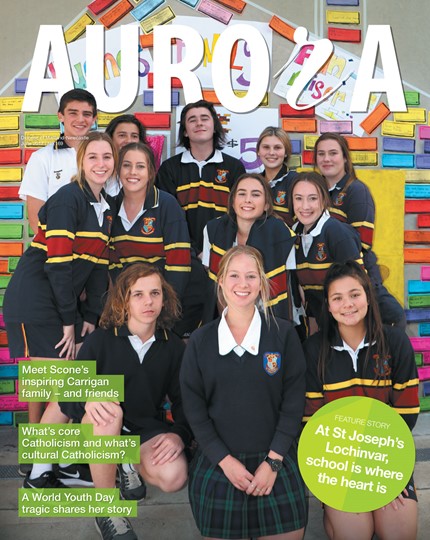

Recently I was with a group of our best and brightest - student leaders from some of our high schools - and I asked what they thought of the survey result. Basically, they all agreed with it. They all knew kids who had suicided or were self-harming, kids who were being treated by psychiatrists or who should have been. In short, they saw young people’s mental health as a major problem.

To me, this is staggering. In my experience of high school, in the 11 years of students who were there during my six years, I don’t recall that there was a single suicide. I don’t think that, even in those days, it could have been covered up. There were ‘sex, drugs and rock-and-roll’ issues but not mental health.

So what has changed? First, my young people thought that the internet had a lot to answer for. One young man said that many kids don’t know how to talk to each other in real life - and are not particularly interested in doing so. Their energies are caught up in online chat or constant gaming. In his Year 12 view, the junior secondary kids are different even from his time, worse in their online absorption. Secondly, some thought that a lot of students struggle with ‘gender issues’.

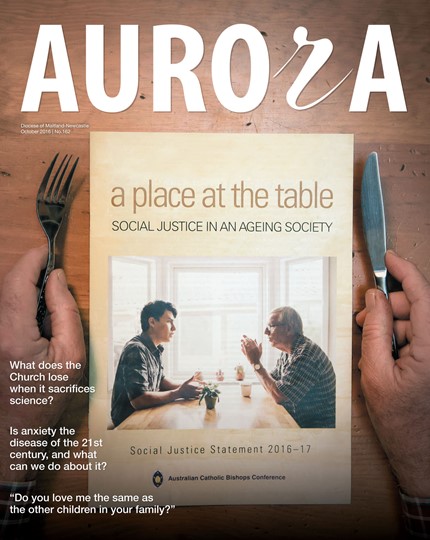

Social commentator Hugh Mackay has a different take on things in his 2013 book The Good Life. He gets stuck into the Utopia Complex, the conviction that, in our age of technical miracles and social enlightenment, everything should be perfect. And I did say should. It’s about entitlement.

As the advertisers would have us believe, ‘You’re worth it’, ‘You deserve it’, ‘It’s all about you’. ‘The real victims of the Utopia complex’, Mackay says, ‘are our children… They might have been so deeply and consistently conditioned to expect the best to be provided for them – admiration and rewards for everything they do… constant support and guidance… - that their arrival on the threshold of adulthood will come as a shock.’

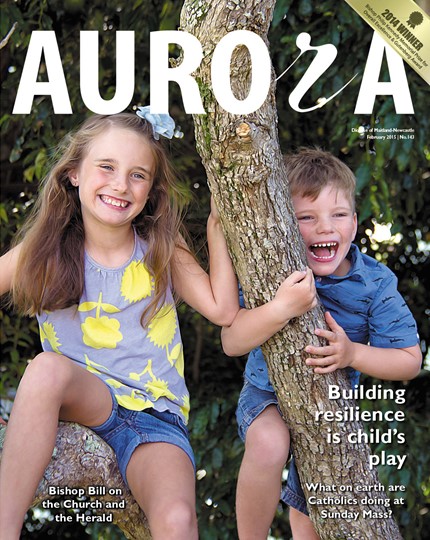

Mackay’s thoughts may look a little dated to teachers. While student ‘well-being’ is a focus in schools, the worship of ‘self-esteem’ is finally and thankfully over and ‘resilience’ is back.

In practice this means that, if you get your sums wrong, it wasn’t a ‘good try’ (even if you didn’t), they’re just wrong and you have to do them again. We’re almost past giving out prizes to everyone for turning up. ‘Resilience’ made its ideological comeback in staffrooms in about 2008. Whether that’s true out in parent-land is harder to gauge.

Now, gender issues. Once it was accepted that boys and girls didn’t like each other until they were about 14 to 16 at which age suddenly they liked each other a lot! Then in the later 70’s homosexuality was decriminalised and, in 1986, officially ceased being a mental disorder.

Awareness of gays in society grew accordingly. By the mid-eighties I was finding that 15- and 16-year old boys who still preferred the company of their mates were thinking they must be gay. Then, in the internet age, 12- and 13-year olds were being expected to state on their profiles whether they were gay or straight. Now it’s a matter of ‘gender’ as much as ‘orientation’ - ‘I know I’m a boy, but I’m in a girl’s body’.

These things, differences in sexual orientation and in gender identification, are real - and it’s good that we handle them better than we used to. But raised awareness puts a lot of pressure on kids who are still developing their identities. How do we deal with that?

I’ve ended with a question, and that’s appropriate. Life has changed a lot in a short time and it’s confusing. But it’s tough on those growing up in the confusion. How can we help? Or is that even the right question? If we were less worried about everything being right in their lives, might they be less anxious when it wasn’t? Or is that question just an old guy not getting how it is now? I wish I knew.