My ‘home’ was half a kilometre away at the Gully Line. It was a place of warmth and love and stability. Because it was so good I didn’t have a restless urge to embark on a ‘ship’ into uncertain waters. I was content with the settled way life was.

This settled way was tested at church camps I attended in my teens. We were presented with two contrasting images of church and challenged to identify which one best represented our personal situation and preference. Were we ‘settlers’ or ‘pioneers’?

In that immediate post-Vatican II era I perceived that we should be pioneers, but my preference was decidedly settler. Home, being a settled place, a place of firm foundations and solid construction, I had no need nor want to venture.

Two thousand years ago the Church was on fire to venture extensively. It was pioneering like its inspiration and creator. It ventured everywhere very rapidly because it had good news from and about a loving God. This God was so keen to have his love form humanity into a community of salvation and love.

Then Constantine happened. A mighty turning-point in the Christian story and a mixed blessing.

When church and state began morphing under the Emperor there was impetus for much of the pioneering – evangelising – to give way to settling. Both facets of church continued of course, but there was now the possibility for settling to gain ascendancy over evangelisation.

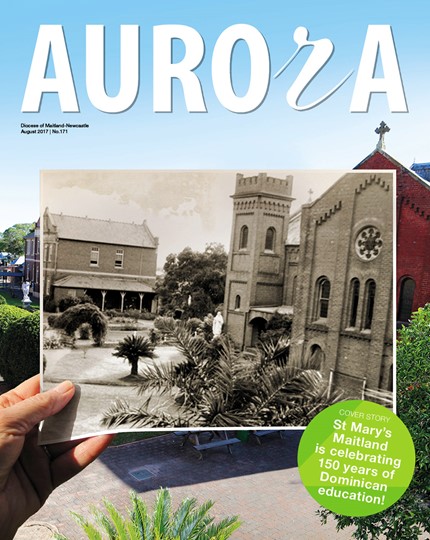

The state gifted the church with churches. The church community began to meet in church buildings.

Over time the word ‘church’ came to mean both the assembly of God’s people (as it had in the Hebrew scriptures), as well as the building in which they gathered for worship.

Such bricks and mortar suited well the needs of the Empire. The buildings represented order and stability set against pagan and barbarian chaos. Prestigious, awesome structures served the political agenda as much as the ecclesiastical. The more state and church coalesced, the more ground was covered in masonry and the taller the spires. Western civilisation is rich in magnificent cathedrals like Chartres and Notre Dame.

What would it have looked like without a Constantine? How would God’s people have developed without such a long marriage of church and state?

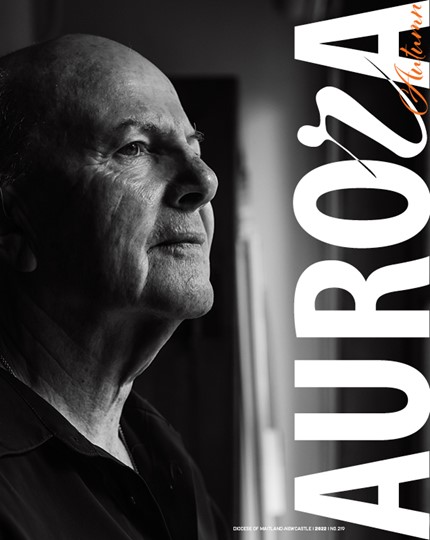

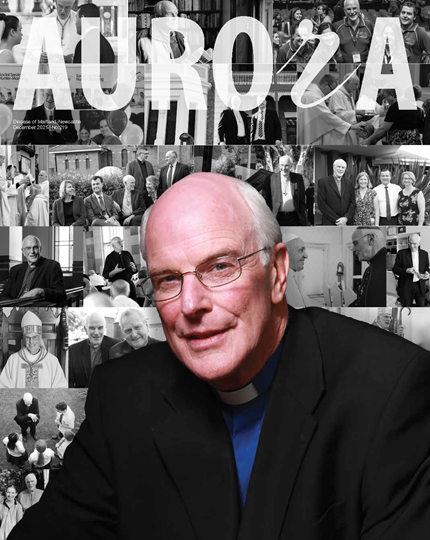

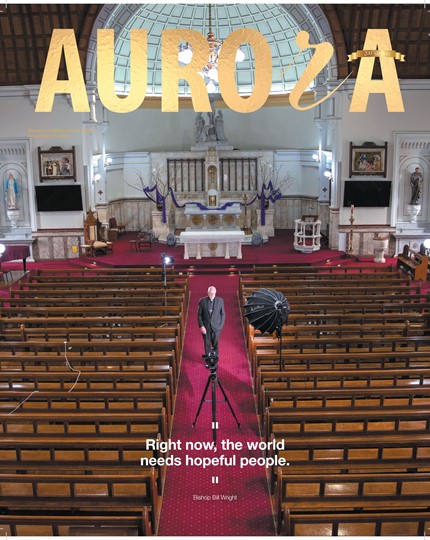

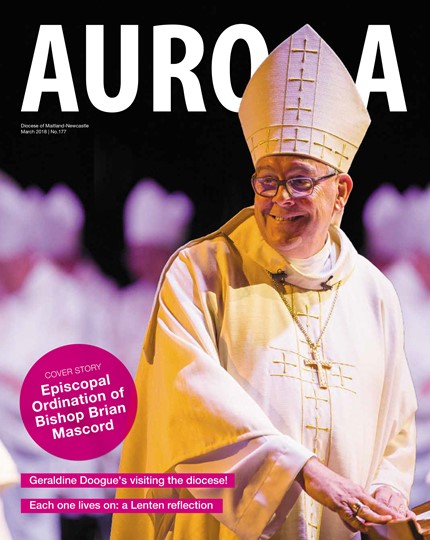

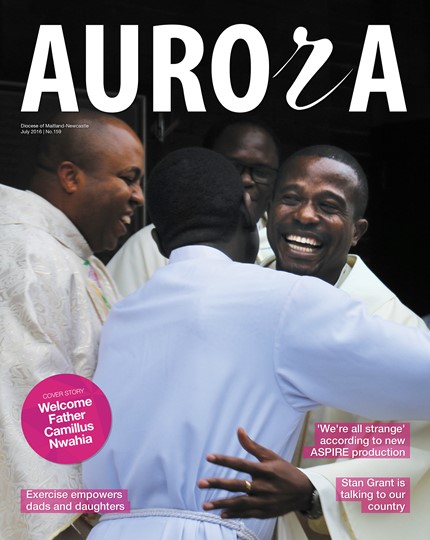

Brian Mascord’s ordination as Bishop of Wollongong has prompted these musings. Brian was enfolded in church on the evening of 22 February. But there was not a single block of consecrated masonry in that place. The nearby church structure could not accommodate the vast number of ‘living stones’ gathered as church to celebrate. The cathedral was empty, but the church was fulsome. People didn’t go to church, they were the church. They assembled where they could be church.

Is there something for us to consider here as we gaze into our future as church? Should we wonder if we have invested more than enough in material ‘churches’ at the expense of building solid communities of beloved disciples? Should we weigh up the relative values of church buildings against living communities when considering restructuring in the diocese? Should we put our energy and finances into forming missionary disciples rather than building maintenance and repairs, let alone new edifices?

Stability and solidity are great things. How do they figure in the mind of the one who had nowhere to lay his head?

Material stability and solidity can foster a significant psychological and spiritual impression. Imperial Rome impressed itself significantly on the shape of the church even up to our time. Have we become too materialistic even in the essential material aspects of our faith?

Have we had a misunderstanding similar to that of St Francis when, standing in the rubble of San Damiano church, he heard the voice telling him to repair the church which he could see was in ruins. Francis found the materials necessary to build walls and roof. But then it dawned that there was a more important church claiming his attention. He and his followers set about to rebuild the Christian people of Europe with preaching and the example of virtuous lives.

No, I am not being iconoclastic. I love our churches. However, I love the church more. I would much prefer to experience the building-up of a people who are well formed, intentional disciples of the Lord who come together on the Lord’s Day to celebrate Eucharist and go from there to spread the good news of God’s love for all. The place they come to, and then go from, is secondary. It could well be an established building, or perhaps a temporary venue as was the case in Wollongong – whatever genuinely best suits the celebrations and the missionary outreach of God’s people.