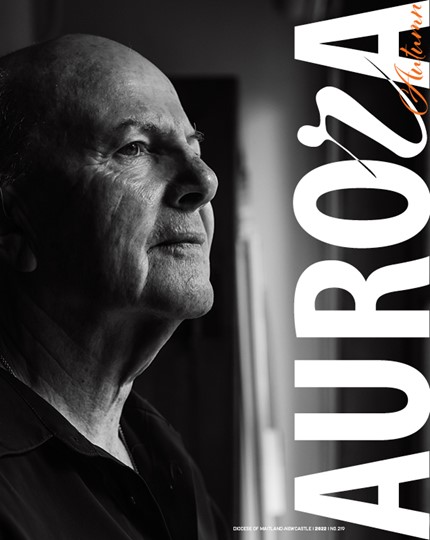

In his late fifties, a friend had a leg amputated and for years afterwards experienced the phenomenon of ‘phantom limb pain’ – he endured bouts of, what he referred to as, ‘real’ pain in the region where his leg once had been. His ‘loss’, of course, meant permanent debilitation and the accompanying pains were superfluous reminders of that fact. The word ‘loss’ is sometimes used euphemistically, frequently being substituted for ‘death’ – one reason that this memory invited the recall and immediate comparison with another – a ‘loss’ endured by my mother-in-law.

On 28 December, 1952, Gerard Archer, the first child of his mother, Laura, came into the world stillborn. Being sedated at the time, Laura never saw her child, never held him. The nuns at Waratah’s Mater Misericordiae Hospital were kind, Laura recalls, while the general demeanour of the doctors could best be described as professional but rather distant and impersonal. Intuitively she understood attitudes towards her situation to be, “Well occasionally, mothers ‘lose’ babies; nature takes its course. So let’s get on with life.” Only the barest of clinical details surrounding this ‘loss’ were divulged.

Especially for a mother, the effects attendant upon such a traumatic happening can be many; effects no less painful, disabling or ‘real’ than the surgical removal of a limb. Two varieties of pain: both psychological; one transient, resulting from a surgical operation with side-effects best labelled ‘medical curiosity’; the other, casting a life-long shadow. For Laura and for many mothers like her, the word ‘loss’ was no euphemism; Gerard’s death was a wrench to her being, a kind of disembodiment. Having carried her son for nine months, in her own words, she “…felt a relationship with him”; his death was “…the death of a part of [her] self”. Hopefully, in this second millennium, death is something which can be ‘faced and embraced’ more openly. In the 1950s it was more likely to be ‘feared and revered’. A mother bereaved in this way was more likely, then, to be met with general avoidance. Apart from the comfort offered by family and friends there was little else.

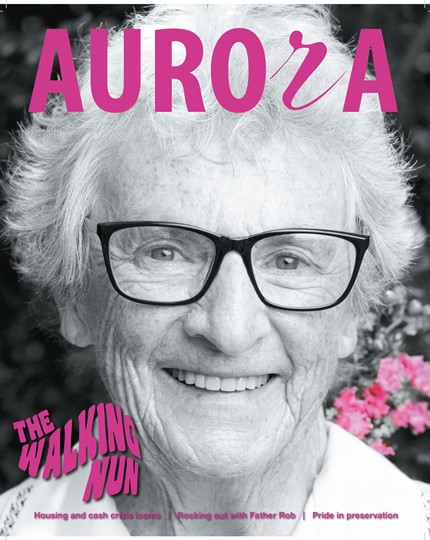

Entering her ninetieth year, Laura retains vivid memories of those years. “They were good times overall,” she says. “In a way, Gerard has never gone; the memories are always there.” She speaks reflectively, expressing touching hints of resignation and tepid nostalgia that overshadow mere sadness. She has long been steeped in her Catholic faith, a faith which, she hastens to explain, led her to an acceptance of Gerard’s death. At age 25 she had been anxious to conceive to fulfil what she saw as the role of a Catholic wife. A sister had already given birth three times, why couldn’t she? She recalls praying fervently for ‘divine favour’ to satisfy her wish for a child. Then, having conceived, Gerard was taken from her. Her instinct was not to rail against fate or God or to cast around seeking others upon whom to put the blame. Her reaction, in stark contrast, was to feel a strong sense of personal guilt. The voices of her faith led her to examine her innermost thoughts and motivations and she came to the clear conclusion that she “…had been putting God to the test”. “I asked myself,” she says, “Who is in charge of my life? Was I putting my will before God’s plan for me? I quickly came to accept that Our Lady needed Gerard more than I did.” In subsequent years four healthy children were to follow. Faith played an integral part in her grieving and healing.

Laura’s faith comes from the heart. “I feel the existence of God,” she says. “The Jesus I know is a humble friend. In the gospels the story of our Lord as a baby is told and how vulnerable and human he seems! That’s the Jesus I talk to.”

There has been an odd parallel to Laura’s experiences in that her youngest son and his wife ‘lost’ their baby son Kyle in remarkably similar circumstances. “So very sad for them; so sad for me,” she says. Old memories had quickly materialised. “Then I saw how, through great sorrow, the whole family coped by facing the reality. Things such as naming Kyle, holding him, taking photographs, the funeral, the anniversaries, the fact of talking openly about him…family, friends, doctors. It seems better these days.” Doubtless, Laura’s particular care and advice at such a critical time played a significant part in that healing. Her own qualities of humility, discernment and an understanding born of experience of how vulnerable we all are, have made her the healer she is. It seems that grieving and healing – like ‘loss’ and ‘reality’ – take many forms.