...andmaybe that’s not a good gauge anymore. Possibly everyone else is watching great stuff over on cable, which I don’t have. For those of us stuck with free-to-air, however, prime time is now a pretty much unrelieved diet of cooking shows, home renos and dating/marrying series. And the worst of it is that these programs aren’t really about cooking or real estate or whatever. Fundamentally they seem to be about what is laughably called ‘reality’, that is to say, the emotional rollercoaster ride that is imposed on, or feigned by, the contestants.

Why do we want to watch fairly ordinary people being driven to tears or screaming at each other, being bitchy or utterly, utterly soppy? I understand why the TV networks love these shows. They don’t have a lot of cash to throw around these days, and there’s nothing much cheaper to make than a ‘reality’ program. But why do we, in apparently great numbers, want to watch real people acting badly (both senses of ‘acting’) or being brought to tears? And who benefits from the creation of a society of emotion junkies? It’s seventy years since George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” explained how sloppy language led to sloppy thinking, making the populace easier to manipulate. Is training people to live on contrived emotional drama a strategy to wean us off the hard work of actually thinking?

The phenomenon is probably more innocent than that. The dominant strand of the western tradition, back to the Greeks, is that our lives should be guided by reason, not by emotion, by thinking, not by feeling. From time to time the culture goes through a bit of a reaction against that austere intellectualism. And now is apparently one of those times. We seem to have decided that living by our emotions is generally a good thing.

Of course there are downsides to the belief that expressing what you are feeling is good and natural. A lack of practice in restraining our emotional reactions is far from an obvious good in society. Combined with individualism, and sustained by the advertising mantras that I really ‘deserve’ everything I want and that I am the most important person in the world, lack of emotional control, not surprisingly, gives us daily instances of road rage, screaming tirades − and worse. If I’m feeling really bad, why shouldn’t I take it out on you? ‘It’s no good bottling it up’, after all. Except, of course, that often it’s a good thing to exercise some control over your impulses, if you’ve ever had the good fortune to learn how.

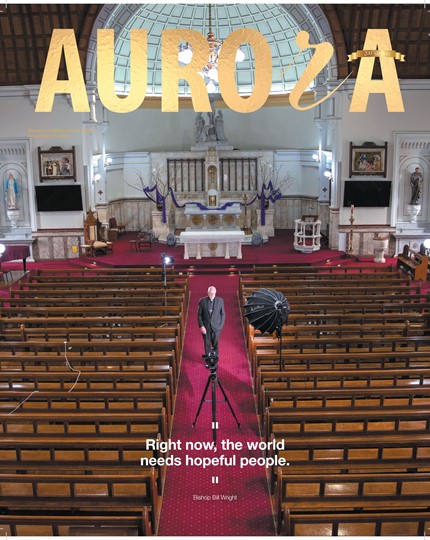

The tendency to be guided by emotions rather than thought or reason is a bit of a problem for religion, too. Of course there is an important place for emotion in our religious lives, as many popular devotions attest, not to mention the rich and deep mystical tradition. But it is not the purpose of our faith to gratify our emotional needs. At the most obvious level, for example, it is not the purpose of our worship to make us feel good. We come together in worship to give praise and glory to God. If I also feel some elevation of my spirits, so much the better. But the dear old ‘I don’t get anything from it’ is really cart-before-the-horse stuff. Time in prayer or worship is a rational reaction to the existence and the goodness of the Creator and Redeemer. It’s one of the many things in life that is not ‘all about me’.

A more serious problem that an excessive focus on my feelings brings into religion, however, is the misunderstanding of conscience. In Catholicism there are two acceptable senses of ‘conscience’ that I can think of. One is Newman’s ‘voice of God in my soul’ or St Ignatius’ ‘good spirit’. To be guided by conscience in this sense takes considerable faith and experience, because it is a matter of being able to truly discern the voice of the ‘Other’ from the inner voices that are merely my wants and needs, my feelings. The other sense of ‘conscience’ in our tradition is that it is a use of reason to determine what is right. It is hard, and prayerful, thought about such things as how my act will affect others, how would it be if everyone acted like this and is this an appropriate way for a human being to behave. In either of these proper senses, ‘conscience’ is, in Catholic tradition, the supreme law: you must follow your conscience. Cardinal Pell was, strictly speaking, wrong to deny that. But I have some sympathy for his reluctance to say ‘just follow your conscience’ when that is now so readily taken to mean ‘Well, you do whatever you feel is right,’ What we’re ‘feeling’ is often not the best guide. The road rage guy is feeling righteous indignation, feels he is ‘in the right’, presumably. But he still shouldn’t rip off your mirror. The human thing is to struggle to do what’s right, and that is often not what we feel like doing at that moment. I’m still with the Greeks on that.