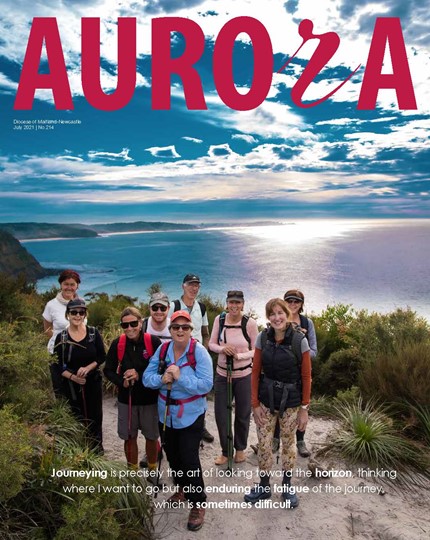

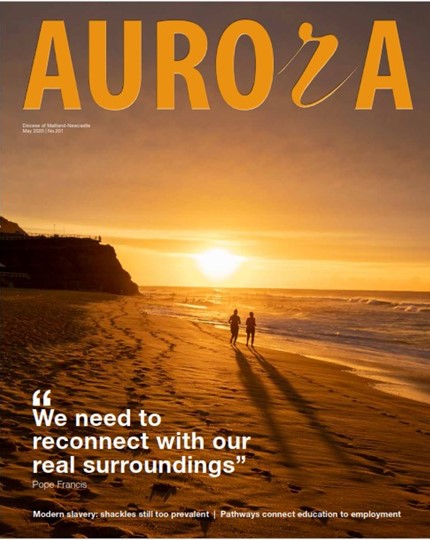

Is there a difference between pilgrimage and tourism? The large numbers of medieval Christians visiting Christendom’s most important sites in the Holy Land, Rome and Santiago de Compostela or revered local sacred places made no distinction between their ‘Club Med’ experience and the religious activity of pilgrimage.

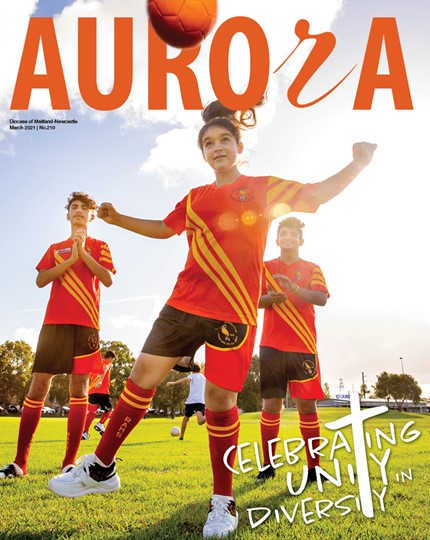

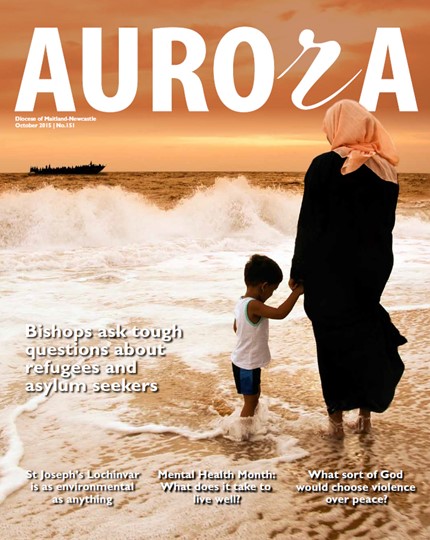

Pilgrimage has been a constant in human existence, well before Christianity, with women, men and children, elderly and young, the well and the sick, the hopeless and the hopeful, journeying to sacred places and shrines near and far, at particular times and seasons and engaging in associated rituals. This sense of movement is connected to something deep within us: the inescapable realisation that human life is a journey. There is a purpose to this journey, a pilgrimage towards God, with God, and in God. While we may be hard pressed to name it, our understanding of life and of faith urges us forward, mindful that wherever we are at any given moment, being led through deserts and seas, our ultimate destination is in God.

Every pilgrim path carries risks, rewards and responsibilities. No matter how well prepared we think we are, it is an arduous journey, with disappointments, mistakes and unexpected setbacks. Graces and blessings abound, seemingly unearned or undeserved; pilgrims may be moved to silence, simply overwhelmed: “I rejoiced when I heard them say: ‘Let us go up to God’s house’” (Ps 122). Tapping into human vulnerability, a pilgrim learns to let go of the belief that if only she can “get it together”, all will be well. Who cannot fail to be moved by the sheer faith of the many suffering pilgrims in Lourdes? Pilgrimage celebrates memory and hope in a way that enriches the soul and nourishes identity.

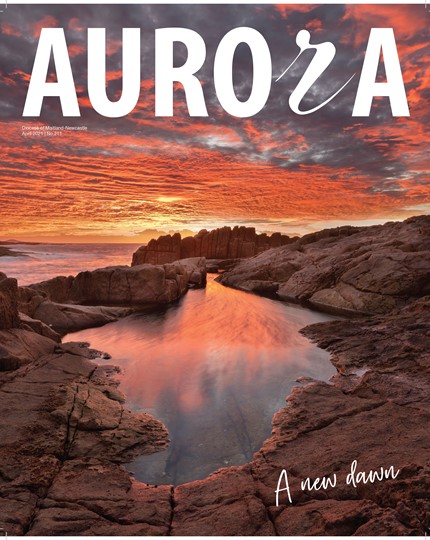

The outer journey is an expression of our inner journey, a response to a spiritual thirst that is prompted by God’s grace. Pilgrimage is praying with our feet (or by air or coach), consciously making a journey that stimulates the eyes of the mind and the ears of the heart to the movements of the Spirit as we work, eat and sleep, which, for most people, is ordinary living. Such mindfulness is a potent result of pilgrimage, learning through experience that living deeply in the present moment is the place of encounter with God. Pilgrimage itself is an act of worship.

Wise walkers on the Camino carry little in their backpacks, and off-load, literally and figuratively, unnecessary ‘stuff’. Learning to travel lightly is a reminder that it is in Christ “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). The call to conversion and a desire to be reconciled with God, Church and neighbour are expressed through popular piety (hymns, processions, prayers of thanksgiving, supplication and blessings; stations of the cross; labyrinth walking, a means of journeying locally when a longer pilgrimage is impossible), and celebration of the sacraments of Penance and the Eucharist. They are essential affirmations of this journey in faith. Of course, liturgical celebrations should nourish and edify. Unfortunately, the noon pilgrims’ Mass at Santiago Cathedral is conducted entirely in Spanish, compromising what should be a significant moment for all who have ‘made it’ to the tomb of the apostle, St James. A gospel proclamation alongside a short Spanish homily, each translated into several languages, would meet this basic requirement.

Like our pilgrim ancestors in faith, the Israelites who were led out of the foreign land of Egypt, the prophets in the Old Testament and Christ, the Blessed Virgin Mary and our Saints who mark the way forward, we are always being called back to our true homeland. Vatican II’s Lumen gentium affirmed that “on earth,” Christians “are pilgrims in a strange land, tracing…the paths Christ trod.” At the shores of the Sea of Galilee, the famous Thomas Cooke, in his Tourist Handbook to Palestine and Syria (1876), offered a moving reason for first-hand travel to sacred places: “Upon those waters He [Christ] trod; those waves listened to his voice and obeyed; from one of those rugged hills the swine fell into the lake. Every place the eye rests upon is holy ground, for it is associated with some most sacred scenes from the life of the Master; everywhere the gospel is written upon this divinely illuminated page of nature, and the very air seems full of the echo of his words.” Cooke’s description reflects the joy and awe anticipated in “being there” where the very reality is engaged and experienced as sacred. Perhaps tourists who come to “sight-see” become pilgrims in the process of “site-seeing.” It is the experience of the presence of God that makes certain places “holy”. The Church believes that Christian shrines and churches have great symbolic value as icons “of the dwelling place of God among us” (Rev. 21:3). They have “always been, and continue to be, signs of God, and of God’s intervention in history. Each one of them is a memorial to the Incarnation and to the Redemption” (Code of Canon Law).

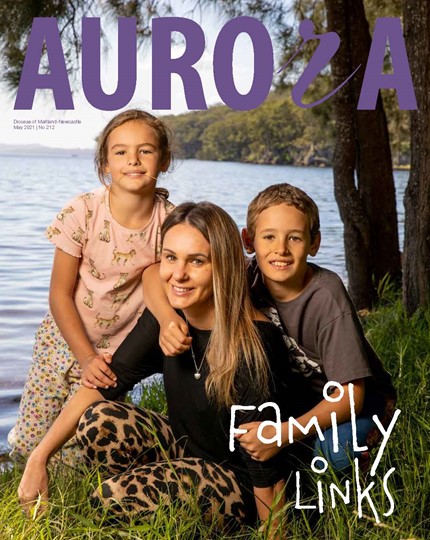

Christian pilgrimage is never a solitary journey. We journey as a pilgrim people and come to learn that we are in the company of all other peoples and nations who are our sisters and brothers, including those who have gone before us. Praying for the dead has always been a hallmark of Christian pilgrimage on earth. In the Mass, the pilgrim people of God is the Church, the Body of Christ that moves towards its ultimate destination, the heavenly banquet that awaits each of us still travelling towards the promised land.

Veronica Rosier OP, PhD, lectures in Liturgical and Sacramental Studies at the Catholic Institute of Sydney and the Broken Bay Institute/University of Newcastle. She is a volunteer guide for Catholic Mission’s Pilgrimage on the Camino.